PenPal Schools Evaluation

PenPal Schools is a web application that enables “creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and discussion” through Project-Based Learning (PjBL) and an emphasis on global-citizenship (PenPal Schools, 2020). It is used by schools in over 150 countries and allows students (8 and older) to engage with other learners in “thoughtfully designed, collaborative projects” (Wilson, 2018). These projects are offered in many of the core subjects along with others such as Environmentalism, Social Justice, and Current Events (PenPal Schools, 2020). They involve “self-guided, differentiated and mixed media” lessons based on a chosen topic (Wilson, 2018). In the lessons, learners read and analyze texts, watch videos, share ideas in a forum space, and collaborate all while “[building] empathy, curiosity, and respect” (PenPal Schools, 2020). The team at PenPal Schools curates each lesson to align with different international educational standards in the areas of “reading, writing, digital citizenship, and social-emotional skills” (PenPal Schools, 2020). Teachers sign up for PenPal Schools and receive their first topic for free (more topics can be obtained through referrals, fees, or scholarships) (PenPal Schools, 2020). In regards to safety, students can only join through a teacher invitation and the only personal information required is the student’s first names, last initials, and country. Every post is moderated and student safety is the application’s number one concern. Click here to dive deeper into the key features, safety, and cost of this multimedia app. Through the integration of PjBL, global citizenship, and multimedia, PenPal Schools provides students with the ability to connect with similar aged children around the world thus enhancing their cross-cultural respect, sensitivities, tolerance, and worldview.

In 2015, President Barack Obama said PenPal Schools was one of the world’s leading social enterprises (Wilson, 2018)! The program also received a “Top Pick for Learning” award in 2018 from Common Sense Education (PenPal Schools, 2020).

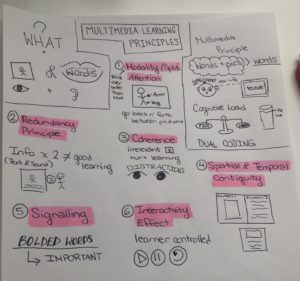

Multimedia Principles

PenPal Schools expertly crafts a multimedia learning environment that fosters the growth of knowledge on a global scale. Since each topic includes videos and readings that incorporate a mix of visual and auditory components, the Multimedia Principle is present (Mayer, 2014, p.8). Each forum section provides potential information to be used in the writing prompts along with worked examples to help students create a resource on a given topic (Mayer, 2014, p.9). Helpful hints and worked examples guide students (Guided Discovery Principle) towards certain learning outcomes, allowing each topic to expand learners’ worldviews while teaching them critical literacy skills (Mayer, 2014, p.9). The website is designed for learners of varying abilities, evidenced by the different difficulty levels within each topic. These levelled resources establish the Coherence Principle as extraneous information and resources are left out of a students’ dashboard (Mayer, 2014, p.8). All of this creates a user-friendly learning platform that allows learners to feel confident enough to explore new topics and share their ideas with their penpal. Each pairing works through a topic at their own pace (Segmenting Principle): watching videos, doing readings, responding to prompts, and creating an end project (Mayer, 2014, p.8). PenPal Schools is a useful multimedia-based, learner-centred tool, that integrates technology organically and authentically.

Collaboration

PenPal Schools works to create a collaborative learning experience that is safe, interactive, and engaging. Through the lessons, students can “[build] on” their own existing knowledge by learning from the provided videos, readings, and experiences of their penpal (Van Den Bossche et al., 2006, p.494). Van Den Bossche et al. states that collaborative learning “…offers poss ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019).

ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019).

Project-Based Learning

An important facet of PenPal Schools is its foundation in project-based learning (PjBL), a “type of inquiry-based learning” that emphasizes student choice, autonomy, and self-reliance (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.268-269). PjBL leads to meaningful learning experiences through its basis in the following constructivist ideas: “learning is context-specific,” “learners are involved actively in the learning process” and goals are achieved “through social interactions and the sharing of knowledge and understanding” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.267-268). Key aspects of PjBL are “time management”, encouraging thoughtful learning, “establishing a culture that stresses student self-management”, connecting with community members, using technological resources effectively, and using varied assessment methods (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.273-274).

Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom.

Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom.

Global Citizenship

PenPal Schools promotes global citizenship by connecting students around the world through the exploration of various topics that build a “global awareness…[and] interconnectedness with others” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.26). While traditional classrooms may overlook current or social justice events, PenPal Schools provides educators with opportunities to tackle global issues that “[are] simply too important to be dominated by other curricular imperatives” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.47).

Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

Alicia M. from Saraland Elementary School says PenPal Schools “creates an understanding of culture differences!”

PenPal Schools provides opportunities to connect with other learners around the world, share experiences, and explore project-based learning collaboratively, all of which are “key to becoming an educated global and digital citizen” (Bjelde, 2020).

– Ms. Bjelde, Ms. L. McLean, Ms. A. McLean, Ms. Gustavsson

References

Katzarska-Miller, I., & Reysen, S. (2019). Educating for global citizenship: Lessons from psychology. Childhood Education, 95(6), 24-33. doi:10.1080/00094056.2019.1689055

Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267-277. doi:10.1177/1365480216659733

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning(2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369

PenPal Schools. 2020. A Global Project Based Learning Community. (n.d.). Retrieved June 13, 2020, from https://www.penpalschools.com/index.html

Schweisfurth, M. (2006). Education for global citizenship: Teacher agency and curricular structure in ontario schools. Educational Review: Global Citizenship Education, 58(1), 41-50. doi:10.1080/00131910500352648

Van den Bossche, P., Gijselaers, W. H., Segers, M., & Kirschner, P. A. (2006). Social and Cognitive Factors Driving Teamwork in Collaborative Learning Environments: Team Learning Beliefs and Behaviors. Small Group Research, 37(5), 490–521.

Wilson, L. (2018, May 03). Everything You Need To Know To Get Started With PenPal Schools. Retrieved June 13, 2020, from https://hundred.org/en/articles/everything-you-need-to-know-to-get-started-with-penpal-schools

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humor, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals.

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humor, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals. Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).

Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).