Part 1: Completion of and Reflection About 4 Different Optional Course Activities

Optional Activity #1: Webinar with Dr. Barbara Brown

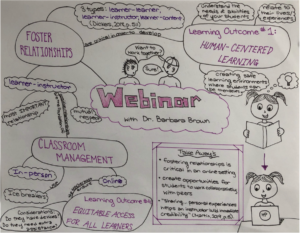

I was inspired to join the webinar by Dr. Barbara Brown as my first optional topic because I was unfamiliar with how teachers could foster relationships in an online setting. Prior to this presentation, I did not believe that this was possible, however, Dr. Brown exemplified numerous ways to support student relationships which has completely changed my perspective of online learning.

I created a mindmap that summarizes the key points of Dr. Barbara Brown’s seminar.

Optional Activity #2: Padlet Discussion Board

I have created this infographic to summarize my experience using Padlet for my second optional activity. I asked the question: How might we support students who have learning designations in an online setting who may not be able to work independently in an online setting? What are some tools that teachers have used to work with those students, especially throughout the pandemic?

Created using Canva.

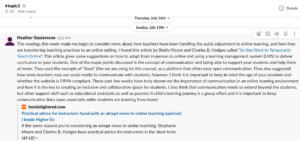

Optional Activity #3: Slack Conversation

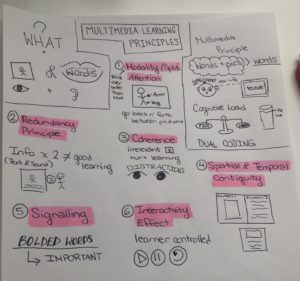

Please watch the YouTube video below which summarizes my experience using Slack to communicate with classmates. To read my initial post on slack, look at the picture below! I wanted to participate in this conversation as I was curious about what my peer’s responses would be like!

My first post on our #EDCI339 class discussion board.

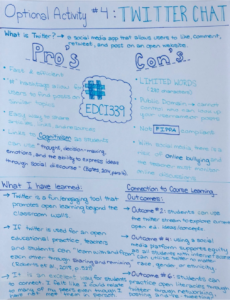

Optional Activity #4: #EDCI339 Twitter Chat

I chose to take part in the EDCI 339 Twitter Chat as I had never used Twitter before, and I was curious as to how a social media platform could support meaningful discourse in an academic setting. I was pleasantly surprised by how quick, efficient, and inspiring it was to connect with my fellow classmates and discuss relevant topics and gain their perspectives.

Sketchnote of class twitter chat from July 23rd, 2020.

Part 2: Updated and Revised Blog Post #3

Click on the links below to access my three original blog posts!

I decided to revise my third blog post for the final assignment. Click here to view evidence of the updated blog and the edits I made to it.

Topic #3 Blog Post

As educators, it is our responsibility to provide equal opportunities for all students and do our best to meet their needs despite social, cultural, or economic backgrounds. Challenges often arise when moving to an online setting as discussed in topic 2, the importance of fostering relationships. This week’s readings provide key examples of how to reach out and support all students in meaningful and relevant contexts.

Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

In chapter 43 of the “Handbook of Research on K-12 Blended Learning Second Edition”, Bashman et al. (2018) discuss the framework of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) which was initially developed as “an approach for ensuring the effective inclusion of students with disabilities and diverse learning needs” but now applies to all learners (p.477). One of the main objectives of UDL is “harnessing technology and instructional practices to remove barriers in curricula and across… learning environments”(Bashman et al., 2018, p.480). The UDL guidelines have been broken down into 3 main principles: why, what, and how of learning.

- Multiple means of engagement refers to the “ways to support the affective state and motivational connection to learning”(Bashman et al., 2018, p.483). This may look like giving students autonomy, agency, and motivation with tasks or assignments around the classroom.

- Multiple means of representation refers to the“ways that we sense and perceive information “recognition” networks that occupy the posterior regions of the brain”(Bashman et al., 2018, p.483). An example of this might be adding subtitles to videos so that students who are learning English can read along.

- Multiple means of expression and action refers to the “ways that we organize and execute strategies and actions through executive and motor cortices that occupy the frontal lobes”(Bashman et al., 2018, p.483). A teacher can allow students to represent their learning in a different format such as a video instead of an essay.

Please watch this quick video that explains the UDL Guidelines and how they benefit all types of learners!

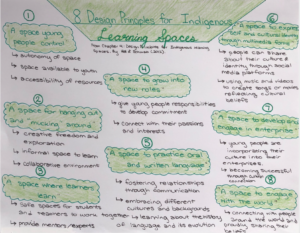

In the second reading, Kral and Schwab (2012) discuss the eight design principles taken into consideration when designing a learning environment. The focus of this article is on Indigenous youth in Australia and their “access to resources and a space that is conducive to the enactment of literacy practices” (Kral & Schwab, 2012, p.59). I think this is a critical aspect that Canadian educators must consider as there is a large population of Indigenous students who need a safe place to create, explore, and learn with access to proper resources and supportive teachers. These concepts are also supported by O’Shea et al (2013) who state that “educational disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous are manifold and similarly reflect a range of social, cultural, and economic imperatives” (p. 394). In this article, the authors reflect upon the AIME program (Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience), where mentors “encourage continued participation in education and to consider university as a viable life goal” (p.392). I think that Indigenous students in Canada could utilize a program such as AIME to further their education. Many rural cities in Canada may not have subject area experts and I think having a digital mentorship program where students could connect over their passions with experts could be very successful.

Here is a list of the eight design principles for Indigenous learning spaces and some of the key takeaways I gathered from the reading.

The third website looks at how online learning has impacted classrooms during the current Covid-19 pandemic. Selwyn (2020) discusses some of the problems that have arisen over the past several months with a quick adjustment to online learning. He highlights how emotionally challenging online learning can be and how “the limitless and abundant nature of digital technologies, teachers and students are finding that remote online schooling requires clear boundaries in order to be manageable” (Selwyn, 2020). It is easy to be overwhelmed by the capabilities of the internet, but in order to deliver authentic learning experiences, teachers must prioritize the emotional well-being of their students. Selwyn further comments on the concept of mental health and the toll it has taken on both staff and students. Taylor and Graham (2020) look at the COVID 19 pandemic and how teletherapy “offer[s] the advantage of providing relatively easy access to services typically at lower cost compared to traditional face-to-face” (p.1155). Teachers must remember that students are also humans with fears and worries and while we are not mental health professionals, we can be the contact person to connect them to resources. I am curious to learn more about the impact of the pandemic on students and how the return to class progress will affect everyone.

That concludes my assignment three “Digital ePortfolio”. Please watch the video below as I reflect on my experience in EDCI 339 and my personal connections to Topic 3!

– Ms. G 🙂

Resources for Optional Activities and Blog #3 Re-Write

[AHEAD]. (2017, November 2). What is Universal Design for Learning (UDL)? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AGQ_7K35ysA

Basham, J.D., Blackorby, J., Stahl, S. & Zhang, L. (2018) Universal Design for Learning Because Students are (the) Variable. In R. Ferdig & K. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (pp. 477-507). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University ETC Press.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Gagnon, K., [Tedx Talks]. (2012, October 17). Learning to listen: Karyn Gagnon at TEDxWinnipeg [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJRmuC6ba1c

Kral, I. & Schwab, R.G. (2012). Chapter 4: Design Principles for Indigenous Learning Spaces. Safe Learning Spaces. Youth, Literacy and New Media in Remote Indigenous Australia. ANU Press. http://doi.org/10.22459/LS.08.2012 Retrieved from: http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p197731/pdf/ch041.pdf

Martin, J. (2019). Building Relationships and Increasing Engagement in the Virtual Classroom: Practical Tools for the Online Instructor. Journal of Educators Online, 16(1), n1.

O’Shea, S., Harwood, V., Kervin, L., & Humphry, N. (2013). Connection, challenge, and change: The narratives of university students mentoring young indigenous australians. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 21(4), 392-411. doi:10.1080/13611267.2013.855863

Selwyn. N. (2020). Online learning: Rethinking teachers’ ‘digital competence’ in light of COVID-19.[Weblog]. Retrieved from: https://lens.monash.edu/@education/2020/04/30/1380217/online-learning-rethinking-teachers-digital-competence-in-light-of-covid-19

Smeda, N., Dakich, E., & Sharda, N. (2012). Digital Storytelling with Web 2.0 Tools for Collaborative Learning. In Okada, A., Connolly, T., & Scott, P. J. (Ed.), Collaborative Learning 2.0: Open Educational Resources (pp. 145-163). IGI Global. http://doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-0300-4.ch008

Taylor, C. B., Fitzsimmons‐Craft, E. E., & Graham, A. K. (2020). Digital technology can revolutionize mental health services delivery: The COVID‐19 crisis as a catalyst for change. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(7), 1155-1157. doi:10.1002/eat.23300

ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019).

ibilities to learn from other viewpoints” by understanding that while another person’s views may differ from one’s own, those views are still legitimate and worthy (2006, p.496). PenPal Schools offers an opportunity to listen and share with friends across the globe and develop those conversations into collaborative projects involving both students’ new learning and their pre-existing viewpoints. A teacher, Jillian W., supports this by stating that “students [connect] globally on PenPal Schools to collaborate and learn together” (Common Sense Education, 2019). Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom.

Tying digital multimedia tools into PjBL allows students to “comfortably engage with the process of designing and developing their project” and being able to easily share and document their creations in “a digital format” (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.272). For elementary ages, PjBL improves “experiential reasoning and comprehension of relations,” content knowledge and group work skills, motivation, positivity in the classroom, and literacy (Kokotsaki et al., 2016, p.269-270). PenPal Schools is an effective tool for the implementation of PjBL into any classroom. Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

Learning about different countries around the world allows students to gain a better understanding of humanity and appreciate the similarities and differences between one another. The goal of globalized education, and PenPal Schools, is to form “a greater understanding of interconnectedness between self and world, skills and values” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.31). By connecting with other cultures, students can learn to empathize with others and work towards “sustainable development and peaceful societies” (Schweisfurth, 2006, p.42). PenPal Schools makes it easy for teachers to integrate global awareness into their classrooms by increasing their “global content,” “[supporting] the idea of student-perceived awareness,” and “[encouraging] student connections” (Katzarska-Miller & Reysen, 2019, p.28). While global citizenship may not be a concrete part of the BC Curriculum, teachers must integrate PenPal Schools or other similar multimedia technologies to work towards a more inclusive world.

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humor, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals.

objectives require different visual formats. Initially, the purpose of static illustrations is examined and it is found that “adding static diagrams or illustrations to a verbal (text or audio) presentation frequently facilitates a deeper understanding of the to-be-learned material” (Butcher, p.181). An article by Kari Jabbour (2012) supports this claim by investigating the types of graphics that foster deeper levels of learning. For example, decorative graphics are often “used to inspire instructional display by adding artistic appeal or humor, but [have] no real instructional target” (Kari Jabbour, p.13). When incorporating graphics in a lesson, it is critical to eliminate unnecessary information and have an equal balance of text and visuals. Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).

Instructional Design and the importance of understanding your unique learners. Shah & Khan (2015) support this idea by stating “multimedia [tools] provide a variety of learning styles at the same time to cater to the requirements of different students” (p.350). Butcher summarizes the findings of multimedia visual and auditory stimuli options through the following benefits: simplifying visuals using well organized semantic models, integrating verbal and visual information both abstractly and concretely; using necessary animations/cues/spotlights, considering existing knowledge for connection making, and allowing students to create their own representations when possible (Butcher, p.194-195). Upon reflection on these findings, the implementation of multimedia in the classroom appears to be a viable option for student success. Through the use of multimedia tools, “learners become active participants in the teaching and learning process instead of being passive learners” (Shah & Khan, p.356).